The first thing to realise is our brain isn’t always on our side. Although we like to think we’re pretty autonomous, we often act by default, without any understanding of why we think and behave the way we do. We do this because our brain is a pretty efficient organ which likes to take the path of least resistance, making life easy for us in the short term but much harder in the long run.

To understand this, let’s take a look at the three main areas of our brain:

1. The reptilian complex

This is the most primitive part of our brain, so called because it was created when we first evolved as lizards. It controls breathing, sexual arousal, balance, sleep, appetite, and body temperature. As you’d guess from this, its primary function is to help us survive, which it does by identifying dangerous situations and defending its territory. It always acts out of instinct and – most importantly – it automatically overrides the other parts of the brain when it senses we’re in danger.

Here are its main characteristics:

- Instinctive

- Fast-acting

- Fear-based

- Self-oriented

- Risk-averse

2. The limbic system

This was the second part of our brain to develop, controlling the expression of emotion and the processing of long-term memory. It initiates reactions in response to these emotions and memories, and makes its decisions based on how the reptilian brain sees the situation. For our purposes here, the limbic system isn’t as important as the reptilian complex and the neocortex, but it’s still good to understand how it works. It acts as a bridge between our reptilian complex and neocortex, much like a Roman charioteer controls two horses, aligning them so they work in sync.

3. The neocortex

This is the most recently developed part of our brain, evolving as we became more advanced mammals. It controls our higher level thinking, such as language, self-awareness, and intention. It can analyse things, so it’s able to view situations logically and think in abstract terms. This means it can imagine, describe, plan, and calculate future possibilities. Its primary function is to make decisions by processing information, and is the area responsible for storing short-term memories. It’s always over-ridden by the reptilian and limbic parts of our brain when the former senses we’re in danger.

Here are its main characteristics:

- Flexible

- Rational

- Articulate

- Creative

- Conceptual

From these descriptions of the different areas of our brain, you can see we have mental conflicts already set up even before we get out of bed in the morning. Our reptilian brain wants to keep us safe, while our neocortex is interested in taking calculated risks. Our reptilian brain is desperate for us to act quickly to get out of danger, while our neocortex prefers to consider all the options. And our reptilian brain is only interested in our physical functions, while our neocortex prioritises thinking, speaking, and conceptualising. What’s more, depending on the situation we’re in, our reptilian brain tends to predominate.

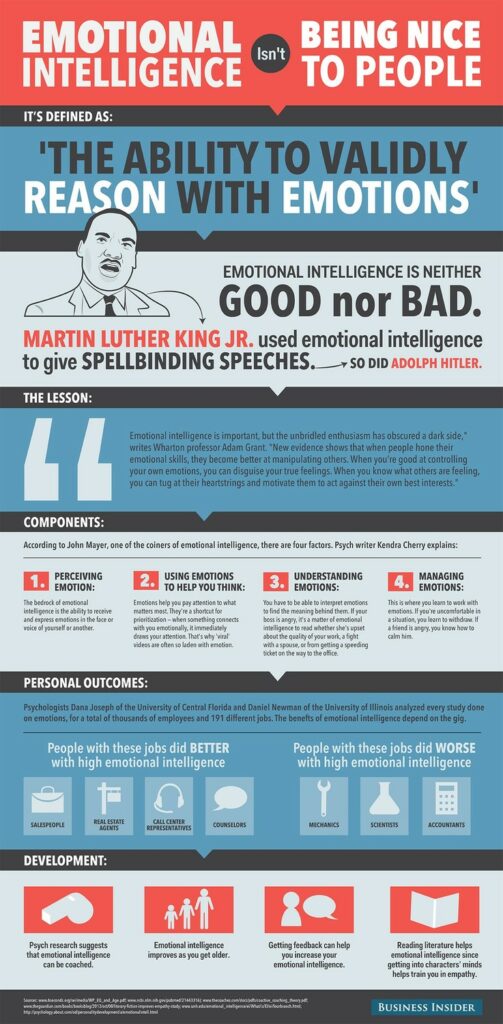

You can see why it can be so hard to build an influential career path when our basic instincts are given free rein, because they work against us being empathetic, visionary and articulate – key traits for fostering strong relationships with others. This is not necessarily bad news for you, though, because through understanding how your brain works, you’ll be one of a select group of people who can use this knowledge to develop resilience, emotional intelligence, and charisma. Let’s take a look at the reptilian complex and the neocortex in turn, and explore how we can make them work both for and against us.

Our reptilian brain

Ever seen a lizard basking in the sun? It seems pretty peaceful until something disturbs its repose. Rather than wondering, ‘Hmm, is that a predator or just a leaf blowing around?’, it takes no chances and scuttles straight under the nearest rock. Our reptilian brain acts just like this lizard. It senses danger (which, in modern terms, is any stressful situation) and prompts our body to act instantly to get us to safety.

From this we can see that everything about the reptilian brain is geared towards keeping us safe; it’s the go-to area whenever we feel threatened, and in order to achieve that it makes us act quickly. The problem is, as high-functioning humans, it can also hold us back because it stops us thinking things through. Imagine you’re a caveman faced with a woolly mammoth on the attack. You wouldn’t want your brain to allow you the luxury of appreciating the beauty of the landscape, or wondering if you had the energy to escape. You’d be desperate for it to shut down all mental functions inessential for your survival so weren’t distracted from the one task you absolutely have to do, which is to run for your life.

Of course, we don’t face many woolly mammoths in our lives today, but someone forgot to tell our reptilian brain that nugget of information. Let’s look at a more everyday example. You’ve had a stressful journey into work; the train was late, leaving you no time to grab your customary coffee and bagel. You feel out of sorts. As you sidle into the office hoping your boss hasn’t noticed your absence, your colleague mentions she was asking why you weren’t at your desk. Damn. But before you have a chance to explain it to her, you remember there’s a meeting you’re supposed to be in which started twenty minutes ago. Double damn. You’re relying on that meeting to persuade Steve, the IT Director, to prioritise the software development which is essential for your new project to shine. Off you rush. Gasping and sweating, you dash into the conference room and take a seat, only to find your agenda item has been skipped. How can you bring it back into the discussion? Maybe you could grab Steve after the meeting, or ask if you could have a slot at the end. What would be best? At this point you notice with horror all eyes are on you. Obviously, someone has just asked you a question but you’ve not noticed what it is, because you were too busy with your stressful thoughts.

I won’t finish the story, as I’m sure you can guess how it ends. Do you get your IT project to the top of the list? I doubt it. This is because, to have an influence over other people, we need de-activate our fast-acting reptilian brain by slowing down. This can feel counter-intuitive and even scary. If we don’t manage to do it, however, we continue to feel under threat, so our concentration becomes a mess and we act distractedly. We go into hyper vision mode, in which we have a kind of tunnel vision because our brain is making us exclude anything not relevant to getting away from danger. You can see how this works against being charismatic and influential, because charisma involves focusing on other people in a relaxed way, and picking up on the subtle social signals they give out. Think of the manager who says his door is always open, but who’s always frantically rushing around; we’re likely to come to the conclusion it’s never a good time to talk to him. Let’s face it, that lizard we saw earlier basking in the sun is probably not great at interpersonal or negotiating skills. And I may be speculating, but I doubt it has many feelings for the lizard sat next to it, or even its own children. It would certainly come last in a persuasive leader competition!

One of the ways we can inspire people is through our creative vision, but acting from our reptilian brain inhibits our ability to be creative. If all we can think about is how we’re going to get through our day, we’re not allowing ourselves the head space to come up with a fresh idea or the time to build a relationship with an important person. If you think about it, this is how human history has developed. In the beginning, survival was our only goal. Then, as we developed surplus food sources and began to create tools and equipment, we turned our attention to more creative endeavours such as education and the arts. This applies in the business world as well. We have to get out of survival mode if we want to be a purposeful and imaginative leader.

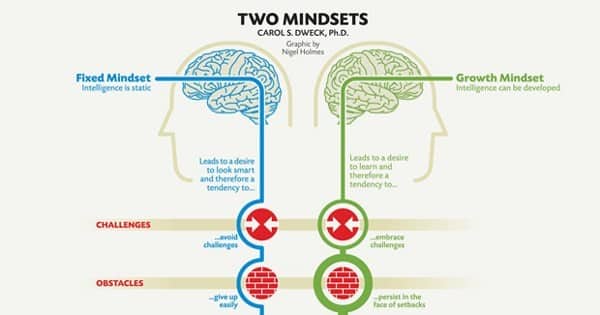

The reptilian brain is also closely linked to having a fixed mindset, which is something we’ll take a closer look at later in the book. A fixed mindset is all about keeping us safe. When we do something in a particular way because we’ve got a good idea of what the outcome will be (in other words, it’s not dangerous), we’ll end up getting the same results we’ve always had. We don’t want to take the risk of doing something different, which might result in us looking stupid or wrong. This not only affects what we do, but what we unconsciously allow those around us to achieve. I’m sure you’ve experienced working for managers who tend to close down your innovative ideas and look for scapegoats when things don’t go according to plan. That’s because they’re operating out of fear, even if they don’t realise it. Their reptilian brain is in charge a lot of the time.

When this fear-based thinking permeates the top of an organisation, it gives a certain message to everyone else: ‘This is the behaviour that gets rewarded. If you want to climb up the corporate tree, you need to be like this too’. In this way, the company culture becomes risk averse. Management might make encouraging noises about being inventive and innovative, but they’re quick to find somebody to blame when something goes wrong rather than use it as an opportunity for learning. Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook shows the opposite approach: the company’s mantra for its developers in the early days was ‘Move Fast and Break Things’. Although this has been modified as the company has grown, the culture is still geared towards encouraging people to try new things even if they don’t go entirely to plan. He doesn’t want his staff to stop taking risks, because if that happens his business will stagnate.

Understanding how the reptilian complex works is also important for developing resilience. When we present it with imaginary scenarios, the reptilian brain doesn’t know they’re not real because it has no imagination of its own. It treats them as reality, and prompts us to act accordingly. So if you’re dreading a particular meeting tomorrow, the more you allow yourself to engage with those worrying thoughts, the more the butterflies in your stomach will grow. You know you want to be more resilient about the whole thing, but you can’t work out how to stop those feelings. If you have more self-awareness, however, you’ll be better able to manage and regulate your thoughts, and be purposeful about them. You’ll tell yourself, ‘These are not helpful thoughts, all I’m doing is agitating myself. I’m going to put them to one side for now’. However, if your reptilian brain isn’t discriminating between these imaginary thoughts and reality, you may not question them at all. ‘I always get nervous before those meetings’, you think. ‘That’s just what I’m like.’

This gets worse when we’re rushed, because stress and hurry stimulate our lizard brain even more. We generate further fearful thoughts, without allowing ourselves the time to register how imaginary they are, or what impact they’re having on us. It’s a vicious circle. Of course, life and work are often busy – I’m not suggesting we zone out and become hippies – but by slowing down and becoming more purposeful, we can bring all our mental resources to a task. What’s more, our brains are incredibly efficient at locking into a particular mode of behaviour. Have you ever found yourself rushing around all week, desperately looking forward to the weekend when you can finally relax? And when the weekend comes, you can’t switch off? That’s because your brain is set into reptile mode. If you work on a production line, having a less active way of thinking can work well. But the higher up the career ladder you go, the more versatile your mind needs to be.

Finally, if we give our reptilian brain too much control, it inhibits the performance of the neocortex – our ‘human’ brain. This is where we do all the good stuff. It’s where our rational thinking and creativity resides; it’s where our short-term memory is located (vital for remembering the names of people you’ve just been introduced to); and it’s the part that gives us our ability to articulate our thoughts to others. These are all elements of thinking which we associate with effective leaders. But when we become agitated, we’re not in control of our reptilian brain. The old lizard says, ‘You think you’re so smart with your pre-frontal cortex, but I’m quicker. I’m taking over’. We become like one of those TV quiz show contestants who can’t answer a simple question, only for it to come to them as soon as the buzzer goes. Doh!

Our limbic system

As I explained earlier, the limbic system in our brain links our reptilian complex with our neocortex. It’s also the area which lays down our long-term memories, so depending on which part of the brain is dominant in a situation, this will inform the nature of the memories we store. Our limbic system even changes the shape of our brains over the years, creating new neural pathways. If we’re not careful, this can encourage us to create a fixed mindset about certain types of experience. Suppose you gave a presentation which went down badly. Your reptilian brain would interpret this as a fear-based situation, and your limbic system would therefore create a scary memory about it. This would tempt you to vow to yourself, ‘I’m never doing that again. I’m going to avoid it at all costs, and if I have to do it, I’ll rush through it as quickly as possible’. If, on the other hand, you got over that fear and gradually built up your experience by making more presentations, your limbic system would lay down new, positive pathways. You’re on track for a growth mindset now.

Our neocortex

Our neocortex is often called our ‘human brain’ because, although it’s found in all mammals, only humans have it in its most developed state. It’s the facility that allows us to pause and reflect, to articulate conceptual ideas, and to be empathetic towards others. As such, it’s key to us developing resilience, emotional intelligence, and charisma. Being the newest part of our brain, however, it tends to be the first function to go out of the window when we’re under pressure. If we were able to act from our neocortex the vast majority of the time, we’d be in a strong position to build influence quickly and easily. Unfortunately, our reptilian brain is so predominant when we’re stressed, this tends not to happen. Much of the following chapters are about how you can train your human brain to predominate over your reptilian brain, but first let’s look at how using your neocortex can help you think your way to the top.

We’ve all been in organisations in which there’s one manager everyone wants to work for. They’re positive, sympathetic, visionary, and creative. Most importantly, they make the people around them feel safe and valued, and as a result they get the pick of all the best talent. Wouldn’t you like to be that person? When you know what motivates people, they’ll go above and beyond their job description because you’ll tap into what’s important to them. None of this happens from your reptilian brain, it only comes from your neocortex.

Our neocortex help us measure our behaviour and thoughts, and also to become consciously aware of how they’re affecting us. For instance, we may come home from a day at work feeling angry or stressed, but not sure why. That’s because we’re in reptilian mode, and it’s our neocortex that allows us the emotional intelligence to check in with our feelings during the day. It also helps us to learn, so we can work out what we’d do differently next time.

Our human brain also enables us to be aware of the comments and behaviours of those around us, because we’re living more in the moment. When we’re in reptilian mode, we tend only to pick up on others’ most obvious social signals because we retreat into a bubble. Have you ever found yourself feeling irritated by your colleagues when you’re trying to get an urgent report written? That’s what’s happening here, and of course, sometimes we do need to be able to shut ourselves away and concentrate. But when this becomes a default position, it stops us building influential relationships with others.

Senior leaders need their people to feel comfortable approaching them when they have a problem or idea; they can’t to be in a tunnel vision state all the time. To develop influential relationships, we need to be alive to these nuanced signals and adjust our behaviour to suit. Our neocortex helps us do this, as well enabling us to to anticipate others’ needs. When we can think, ‘If I do this, what will him mean for him or her?’ we’re using it in a positive way.

Negotiation, selling and persuasion are other key areas for our neocortex. Some people consider these activities from a reptilian viewpoint: one party must win and the other must lose. This can lead us into various unproductive behaviours, such as interrupting people, ignoring them when they say something we don’t like, and arguing with them. This is fear-based, black and white thinking. High-level thinking, on the other hand, means creating a pausing place. Instead of making instinctive assumptions, we give ourselves the chance to reflect on what might be going on behind someone else’s behaviour, or even our own. ‘Is it them, or is it the mood I’m in which means I’m finding that person annoying?’, you ask yourself.

When our neocortex is active, we’re happy to consider ambiguities and alternative perspectives. For instance, if we’re in fear mode and our boss tells us he wants to see us in the morning, we’ll spend all night worrying about what it might be about. ‘I’ve done something wrong, which means I’ll not get promoted, which means we’ll not be able to go on holiday, which means my family will be disappointed … ‘ Before we know it, we’re living months and years ahead in the future, all from one remark. Our rational brain, on the other hand, will see potential solutions: ‘Okay, you’re worried about this. But what could you be focusing on right now so you can get the best possible outcome?’

Our neocortex is also where our short-term memories are stored. I’m sure you’ve experienced the embarrassment of forgetting someone’s name as soon as you’ve been introduced, and know how impressive it is when someone else remembers yours. When we can recall and use these nuggets of information, it makes people feel safe. Which means, if they’re in a position to entrust us with their new project or contract, we’ll be first in line.

Our short-term memory also enables us to be flexible. In most walks of life we can never be completely sure how things will go from moment to moment, especially when there are other people involved. When we can think on our feet by recalling stories or facts from our short-term memory, it helps us build rapport. In fact, when I treat people who have been under stress for long periods of time, one of the things they talk to me about is how they’ve started to forget things. Our human brain is an antidote to that.

Language and speech is another area controlled by our neocortex. I’m sure you’ve noticed when you feel agitated it’s harder to get your words out articulately; that’s because you’re operating from your reptilian brain. But when you feel purposeful and relaxed, your words come out more easily; you’re also more likely to speak from the heart and think things through in a logical and flexible way – both key traits for an influencer. It’s about having flexibility, rather than just one way of coping with the world. When you use your neocortex, you’ve got a range of tools which you can purposefully alternate between.

Creativity is an alternative aspect of our neocortex that helps us to be influential, both in terms of being able to articulate big ideas, and also in the interplay between people. We all have the ability to be creative in different ways, but sometimes that’s best unleashed by being with others. It’s also hugely powerful to allow our colleagues to feel safe enough for them to be sure their ideas won’t be criticised by us, with the result we’re facilitating their thinking as well. Not only that, but being with a creative person who has a visionary approach is inspiring. They’re effectively saying to those around them, ‘Almost anything is possible if you think outside your parameters’.

If I were to ask you where you feel most natural and relaxed, you’d probably say it’s at home with your family or friends. It’s where you feel safe, and as a result you’ll be more open to learning and developing there, rather than in an office where you can never let your guard down. There’s definitely potential in most work places to make a shift towards this kind of atmosphere, which is why some companies are bringing in playful elements such as pool tables and relaxation zones. They bring our neocortex into operation. If you need creativity and intellect to do a good job (and who doesn’t?) then taking time out to be playful and give yourself variety in your day helps re-set your brain from reptile to neocortex.